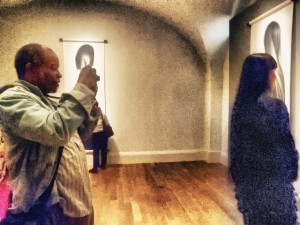

Zhan Chun Hong at the National Portrait Gallery, ©Terry deBardelaben

I was struck by Zhang Chun Hongs’ presence and what appeared, at the time to be, a woman in “command of her gallery”. Tall, statuesque, stately, demure, and stunning. Words that I would use to describe Zhang Chun Hong. I happened upon Zhang Chun when she was being physically prepped- surrounded by technicians, for her 2:00PM presentation at the National Portrait Gallery’s Portraiture Now: Asian American Portraits of Encounter exhibit.

After briefly speaking with the artist before strolling with her to her space I found Jhang to be friendly and very engaging. She broke the ice by approaching us – Jarvis Grant and I. At the beginning of her talk she began telling a very classical story of migration and change. Information about how the artist gave birth to her renown symbolic portraits …streaming charcoal drawings mounted on white scrolls, which give her work a commanding and stately traditional presentation.

Zhang Chun Hong and Terry deBardelaben at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery. ©Jarvis Grant

Zhang Chun Hong’s work, on the surface, appeared ultra feminine. After all, hair— every girl’s nightmare, desire, obsession and preoccupation WAS the focal point. Yet, while I gazed at the striking portraits…I began to think about the bombarding questions provoked by the –black streaming, long flowing meticulously presented hair. But also, I wondered about the artists’ hair-… (Zhang stands approximately six feet tall with hair reaching down to her thighs). The obvious questions pertaining to…hair maintenance, hair care, length of time it takes to grow hair that long, the process associated with washing and drying extra long hair, etc. etc. And Oh, had she ever considered cutting her hair, do her sisters, mother and aunts have long hair? I wondered why in some cultures hair is

“ associated with life force, sexual energy, growth, and beauty”. Why people question the beauty of women with bald or shaven heads? I found myself wondering whether or not Zhang Chun or Hong Zhang as she is known in the US was attempting to make some sort of feminist statement that went beyond the politics of hair. Perhaps her motivation was more about the dominance of the physicality of hairs’ impact on culture, gender and tradition. So-oo, when Hong Zhang began speaking, I hung on to her every utterance.

Her autobiographical work, visually communicated her story was yet conveyed in an extremely intimate setting conducive to the confines of the gallery space. The portraits, wood flooring and small gathering lent itself well to creating an environ that complimented the artists words and story telling allure. Hong Zhang was humorous- recanting funny vignettes about the impact of language and culture on her life. She has a very interesting personal history about her artist DNA. She and her twin were both painters, winners of art competitions and to some measure are predisposed to being artist since both parents are art professors. Before she arrived in Atlanta from Beijing in 1996 with her twin sister, she attended boarding school. They ate their meals together and spent a considerable amount of time together. She is left-handed and her sister right. Other boarders were always fascinated by how much they seemed like one person when they sat eating side by side – one using the left hand and the other the right. It tied in perfectly with her triptych of herself, her twin and the older sister. Mind you these sculpture like portraits exaggerate the length and flow of the dark illumination of the hair, which at times makes one feel as though they are in the presence of statues. Statues with their backs turned only allowing the viewer to engage the posterior view of the hair –with the slightest suggestion of a head. However the unmistakable visual dominance of the composition is the hair…each strand articulated with precise clean lines.

Hong spoke of her East/West triptych having both a Renaissance and Chinese presentation. In traditional Chinese paintings Jhang said that his advisors always flank the emperor. In Jhang Chuns’ triptych –her older sister has the center portrait, and like a traditional Chinese painting which depicts the military advisor to the emperors’ left she symbolically presented her hair twisted toward the because she often took on the role as the fighter-protecting and coming to the aid of her twin.

As Hong stood in front of each portrait she transformed the space with warmth and insight about her life. The behind the scene story of her journey to this country and her constant reference to her work gave those in attendance a brief look at the artist as conveyed through her own lenses.

Terry deBardelaben,

Artist, Educator and Researcher

Jarvis Grant photographing Zhang Hong at the National Portrait Gallery, ©Terry deBardelaben

Zhang Chun Hong, Artist, ©Jarvis Grant